|

Pitcairn Island & Pacific Union College | Seventh-day Adventist schooner Pitcairn |

Pitcairn

Island, in the South Pacific Ocean some 5,000 miles south of its campus, and Pacific

Union College, a co-educational liberal arts institution in California's Napa

Valley just north of San Francisco, have a common religious bond, the Seventh-day

Adventist faith. A conservative Protestant Christian body of some 10 million

members world-wide, the Seventh-day Adventist denomination has, since its founding in

1863, practised the biblical injunction to carry the gospel message "to every

nation, kindred, tongue and people." In harmony with this charge, the church

today is active in practically every country of the world. In 1876, J.N.

Loughborough and James White, two Seventh-day Adventist clergymen who were living

in the Napa Valley, learned the fascinating story of the mutiny on HMS Bounty,

and that the mutineers' descendants were living on Pitcairn Island. They determined

to see that the Pitcairners learned of their Adventist faith. They prepared a

box filled with religious papers, and took it to the San Francisco waterfront

where they found Captain David A. Scribner of the ship St. John who agreed

to take them to Pitcairn. The Pitcairners read the papers sent by the clergymen,

but they made no change from their Church of England faith which they had been

practising since the early 1800s. At that time John Adams, the only surviving

mutineer, had introduced them to religion through a Bible and a Church of England

prayer book taken from the Bounty. In the changed life of John Adams -- from criminal-minded

sailor to peace-loving patriarch -- those on Pitcairn found eloquent testimony

to the Divine power that changes lives. But, as it must to all, death came to

the beloved island leader. The Pitcairn Register Book entry of March 5, 1829,

states simply, "John Adams died aged 65." Sir Charles Lucas in

his introduction to the register book, writes: Many notable

cases of religious conversion have been recorded in the history of Christianity,

but it would be difficult to find an exact parallel to that of John Adams. The

facts are quite clear. There is no question as to what he was and did after all

his shipmates on the island had perished. He had no human guide or counsellor

to turn him into the way of righteousness and make him feel and shoulder responsibility

for bringing up a group of boys and girls in the fear of God . He

had a Bible and a Prayer Book to be the instruments of his endeavour, so far as

education, or rather lack of education, served him. He may well have recalled

to mind memories of his own childhood. But there can be only one straightforward

explanation of what took place, that it was the handiwork of the Almighty, whereby

a sailor seasoned to crime came to himself in a far country and learnt and taught

others to follow Christ.

Given the simple religious

principles and piety Adams taught them, it was natural that the Pitcairners would

have considerable interest in the box of Seventh-day Adventist tracts brought

to them by Captain Scribner, even if their message did not inspire an immediate

change in worship habits. In 1886, John I. Tay, a Seventh-day Adventist

layman living in Oakland, California, who had retired from a seafaring life, went

to Pitcairn. For five weeks the islanders studied with him the principles of the

Adventist faith. They clearly recalled having been introduced to the Adventist

way of worship some 10 years before through the box of tracts they had received.

Almost all on the island decided to embrace the Adventist faith. They asked to

be baptised as Seventh-day Adventist Christians, but Tay, pointing out that he

was not an ordained minister and thus could not perform the rite, promised to

return with an ordained clergyman for the baptism they desired. It was four

years, 1890, before John I. Tay could keep his promise. He returned on the Seventh-day

Adventist schooner Pitcairn in November, 1890. Most Pitcairners, since

then, have been members of the Adventist faith. The Pitcairn made

six missionary voyages into the Pacific from San Francisco. On each voyage, Pitcairn

Island was her first port of call. In connection with several of the voyages,

as the islanders caught the spirit of spreading the Christian gospel to other

lands, a number asked to join the missionaries on the ship who were being assigned

to other Pacific islands. Yet others, realising that they needed formal training,

were brought to San Francisco where they enrolled in Healdsburg College, just

north of the city. Healdsburg College, founded in 1882, was renamed Pacific

Union College, and in 1909 was moved to the mountain-top resort called Angwin's

in the Napa Valley. One of Pacific Union College's women's residence halls is

named Andre Hall. Hattie Andre was the first non-island school teacher on Pitcairn,

having arrived on the island in 1893 on the Pitcairn. A beloved teacher,

Miss Andre taught the islanders the art of basket weaving and wood carving which

today accounts for much of the island's economy. After her service on Pitcairn,

Miss Andre came to Pacific Union College as a dean of women. Thus it is

that Pacific Union College records the names of Pitcairn Islanders among its student

bodies of the past; has developed a world-class study center about the entire

Bounty saga; maintains a women's residence hall named after one of Pitcairn's

most beloved teachers; and is in frequent contact with its many friends on the

tiny South Pacific Island.

The Good Ship Pitcairn

Her beginnings, her crews, her voyages,

her Christian mission, and afterward.

The beginnings:

The headlines were big and bold in the San Francisco newspapers: In 1873 the British ship Ennerdale had arrived at the California port city with the shipwrecked crew of the ship Khandeish aboard. At tiny Pitcairn Island in the deep South Pacific Ocean, the Ennerdale had found the stranded crew, their ship having piled up on the reef at Oeno Island some weeks earlier.

Home were the Khandeish's sailors from their harrowing sea disaster, and the San Francisco press played the story big, including the many kindnesses shown to the crew members by the Pitcairn people. A public fund was started to collect food, clothing and cash for the Pitcairners who seemed to perennially be in need of life's basic supplies.

Reading of the rescue and the islanders' helpfulness, two Seventh-day Adventist clergymen in the Napa Valley just north of San Francisco, donated a box of religious books and other literature to the fund that they thought the Pitcairners might enjoy reading. In 1876, the contributions were delivered to the island by Captains David Scribner of the ship St. John, and Warren Mills of the Eliza McNeil.

Pitcairn school teacher Simon Young, Moses Young, and Simon's daughter Rosalind, and a few others on the island read the literature the two ministers had boxed up, but it held little interest for them at the time. Someone said, "The box of books gathered island dust."

More books from the same source came to Pitcairn on the ships Golden Hunter and Golden Fleece, and this shipment ignited some interest in Pitcairner Mary Ann McCoy. She shared her interest with others on the island. So deep did their interest become that in early 1886, the group separated themselves from the Church of England congregation on Pitcairn and began to worship on the seventh day of each week, the Sabbath. This caused a stir on tiny Pitcairn Island.

Also, in 1886, in Oakland, California, a former sailor and carpenter named John Tay, who in 1874 had become a Seventh-day Adventist Christian, decided to make good on his long-time fascination with Pitcairn Island. He gained workaway passage on the ship Tropic Bird from San Francisco to Tahiti, with the intention of finding a ship there that would take him on to Pitcairn.

After a long delay in Tahiti, John Tay convinced the captain of the British warship Pelican to take him to Pitcairn Island. The law of Pitcairn at the time allowed visits of only a few days, but after learning that he wanted to study the Bible with them, the islanders by unanimous vote waived the law.

John Tay was on Pitcairn Island for about five weeks, and as time came for him to depart, a number of the Pitcairners said they wanted him to baptize them into the Adventist faith. "It would be a privilege to do that," said Tay, "but only an ordained minister of the faith can perform that rite and I am not ordained. But I promise that I'll return, and when I do there will be an ordained minister with me who can baptize those who wish at that time."

Soon after he left Pitcairn on the yacht General Evans, Mary Ann McCoy, the island magistrate's sister, wrote this in her diary:

October 30, 1886. The Church of Pitcairn Island kept the Sabbath unanimously as the day of the Lord. This was the result of a month's labor among us by Brother John I. Tay.

|

|

John I. Tay whose lay missionary visit to Pitcairn Island in 1886 led to the building and the six missionary voyages of the ship Pitcairn.

|

A Plan For The Pacific Mission

On his return to the United States from Pitcairn Island, John Tay appealed to his church's leaders to begin a spread of the Christian message throughout the Pacific Ocean. His plan also included the sending of an ordained clergyman to Pitcairn where his promise of baptism for those who wanted to join the Adventist faith could be fulfilled. The church's response to Tay's appeal was not exactly enthusiastic.

Finally in April, 1888, the church voted to send an ordained clergyman - Andrew Cudney - to baptize the Pitcairners and organize their church. He would also survey other Pacific islands to see if there was a possibility of fruitful Christian activity on them. The plan called for Cudney to go to Hawaii to seek a ship that would carry him to Pitcairn, and for John Tay to go to Tahiti to await Cudney's arrival there. The pair would then go on to Pitcairn.

In Hawaii, Cudney could not find a ship that would take him to Pitcairn. At the point of desperation to complete his mission, and with the financing of N.F. Burgess, a fellow Adventist, Cudney purchased a ship, refitted her, hired a crew of six, and on July 31, 1888, sailed from Honolulu for Tahiti. The ship was named the Phoebe Chapman.

Once out of sight of the Hawaiian Islands the Phoebe Chapman disappeared! She was lost at sea without a trace!

Having waited for months for Cudney in Tahiti, John Tay at last returned to California where he learned of the Phoebe Chapman's disappearance at sea. Though heart-broken when he finally learned of the loss, Tay increased his urging of his church to carry the Christian message to the islands of the Pacific. At last his urging, coupled with the tragedy of the loss of their first mission ship, ignited the church leaders into action.

The church leaders decided to build their own mission ship, with the building of it being watched over by a small committee of seamen who would assure it was built in a sea-worthy way. Children of Adventist parents throughout the United States began a fund-raising campaign that included such childhood money-makers as shining shoes, doing laundry, yard-work and the like to underwrite the ship's cost.

The U.S. West Coast's largest shipbuilder, Captain Matthew Turner was hired to build the ship in his Benicia, California, shipyard. So impressed was he with the ship's Christian mission that he donated $500 to her cost.

|

|

| Visitors aboard the under-construction hull of the ship Pitcairn in the shipyard of Captain Matthew Turner in Benicia, California, in 1890. |

At high tide - 10 p.m. - on July 28, 1890, the newly-completed Seventh-day Adventist missionary ship, named Pitcairn, slid down the ways of the Turner Shipyard into the quiet waters of San Francisco bay. The two-masted, white-hulled vessel, of some 90 feet in length was moved to nearby Oakland, California, where she was rigged and outfitted for the voyages that lay ahead.

The Pitcairn's First Voyage

In the afternoon of Monday, October 20, 1890, John Tay's keeping of his promise to the

people of Pitcairn to return to them was about to begin. Hundreds of church members and other friends gathered on a dock in Oakland to watch as lines were cast off and the missionary ship Pitcairn moved out into the stream that would take her through the waters of San Francisco Bay, and out through the Golden Gate into the vast Pacific Ocean. Her first port of call would be Pitcairn Island, South Pacific Ocean.

On board the ship was John Tay and his wife, Hannah. Pastor Edward H. Gates, along with his wife, Ida, was also on board, as were a third missionary couple, Albert and Hattie Read. The ship's crew included Captain Joseph Marsh; first mate, J. Christensen; sailors, Gustav Alex Anderson, Charles Kahlstrom, and Peter Hansen. The cook was Charles Turner, and the cabin-boy was Nicholas Gathhofner. The crew had been chosen from among hundreds of applicants.

As the ship was leaving the Golden Gate, another schooner struck her, tearing a hole in one of the sails, but not otherwise materially damaging the vessel. The voyage southward down the Pacific Ocean was uneventful save for days of becalming weather and infrequent rain storms. On November 25, Pitcairn Island was sighted. John Tay, after a four-year delay in keeping his promise to the Pitcairn people, was now about to make good on it.

The Pitcairn lay off the Island for three weeks, and during that time eighty-two people who had requested the rite were baptized by full immersion in one of Pitcairn's natural rock pools. Acting on the biblical injunction that pork is "unclean" meat, the Pitcairners destroyed all pigs on the island. Pastors Gates and Reed organized the Pitcairn Island Seventh-day Adventist Church. Several religious societies for youth and women were formed. A tract society was formed in which members would distribute religious literature to the crews and passengers of ships that called at the Island. |

|

| The foot-pedal-driven organ that was used during the six voyages of the missionary ship Pitcairn. |

When the missionary ship departed Pitcairn Island in December, 1890, three Pitcairners, newly baptized church members James Russell McCoy, his sister Mary, and Heywood Christian, were aboard. At their request they were to assist the missionaries as they labored on other islands at which the ship would be calling.

Six days of sailing found the Pitcairn at Papeete, Tahiti. Pastor Gates gained permission to hold a public religious meeting in the town, but it had to be cut short "because of the rowdy interjections and tumult made by opposition. Some brawling developed in the crowd, and one Tahitian was imprisoned for a month."

Despite the tumult of that first meeting, a number of persons enjoyed subsequent presentations. An English-Tahitian blacksmith, Edgar Bambridge, offered to translate one of the religious books carried on the missionary ship - "Bible Readings for the Home Circle - into Tahitian. Among others, Paul Deane, leader of a different Protestant denomination, as well as the deacon of his church, decided to join the Adventist faith.

Moving from Papeete to Raiatea Island, those in the missionary ship had additional success. Religious book sales were made among the Europeans of Huahine Island, where the Pitcairn had called before returning to Papeete. At Papeete, the ship's cook, Charles Turner, left to return to America.

The Pitcairn headed south to Rurutu Island, where they found that the native minister on the island was the son of a Pitcairn woman who was living there. Those on Rurutu listened attentively to the missionaries' presentations, among them the boy-king of the island. Then the ship sailed westward toward the Cook Islands, their first call in the group being at Mangaia Island. Though there was no opening in the coral reef circling Mangaia, the missionaries "jumped" the reef in a dugout rowed by the natives of the island. The steersman in the dugout would watch for the biggest wave, and on his command rowers would paddle fast in the rising swell to take the missionaries over the dangerous reef and safely into the calm waters closer to shore.

The Protestant missionary couple on Mangaia welcomed the Adventist missionaries with open arms. When the group left the island, the harrowing reef "jumping" had to be performed in reverse, with the wash of a king wave spilling over the rim of the reef, allowing the dugout to be swept in its backwash out into the ocean once again.

The next call for the Pitcairn was Avarua, Rarotonga Island. The missionaries Read, and their assistants, the Pitcairners McCoy, stayed at Rarotonga to sell religious literature, while the ship sailed north to Aitutaki atoll. Both groups who stayed on Rarotonga found success in their book selling. James McCoy promptly contacted Frances Nicholas, secretary to the island governor. She bought a book from him, mostly to get rid of him. Later, she became convinced of the Adventist message and served as a translator for the church's Avondale Press in Australia. While in these waters, Pastor Gates of the Pitcairn donated a number of books to the library of the Protestant missionary ship John Williams.

Turning northwest toward the Samoan Islands, the Pitcairn first visited Pago Pago and then Apia. Pastor Gates gained the impression that the Adventists were not welcome. Nevertheless, many English, Scandinavian, French, and German religious books were sold, especially on health topics.

Zig-zagging its way westward across the Pacific the Pitcairn turned south-southwest with the Tongan Islands being the next destination. There many books were sold to European settlers, first at Vava'u, then Lifuka, and finally Nuku'alofa.

The idyllic scenery in the Tongan islands group impressed the travelers. But the scenery gave no hint of the murderous atrocities committed there in the past due to inter-clan wars, and martyrdom suffered by European evangelists of the London Missionary Society nearly a century earlier. Nor did it show the more recent trauma suffered by loyal Methodists exiled for a time from Koro Island, Fiji.

Methodist Pastor Shirley Baker had become Premier of Tonga and the confidant of King George Tupou I. His political involvement led to his dismissal from the church. Taking advantage of a local split which developed, he set up the Free Church of Tonga in opposition to the Methodist Mission. Despite its name, Baker tried to force all Tongan Methodists to join. Communities not cooperating had their schools taken over, gardens destroyed, and persons harassed by the police. An attempt was made on Baker's life. In retaliation, Baker had the culprits savagely flogged. Then the British government stepped in and ordered Baker's removal from Tonga for two years. It was during that interim and comparative calm that the Pitcairn called.

Before leaving Tonga the Adventist missionaries on the Pitcairn visited King George Tupou I, then over ninety years of age, donating some books to his household. A large number of books were sold in the Tongan islands group.

Heading northwest, the missionary ship next called at Fiji, a group of islands were cannibalism had prevailed and Christians had suffered martyrdom. A woman who had come with the Pitcairn from Tonga to visit her father in Fiji introduced the missionaries to a number of leading families in the community. In Suva harbor a number of visitors attended Sabbath worship services aboard the ship.

Soon the Pitcairn sailed for Levuka on Ovalau Island, again leaving the Reads and Pitcairner James McCoy to sell books, while others did the same on Vanua Levu and Taviuni islands, all in the Fiji group. In their book-selling efforts the missionaries found success. They also preached in Methodist churches and were hosted in Methodist missionaries' homes. When the ship returned to Suva, it was decided that John Tay and his wife would remain there to foster the positive response already evident.

The original plan was that those on the Pitcairn would survey interest in the Santa Cruz and Loyalty Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and Norfolk Island, and then visit Australia.

|

|

An artist's painting of the missionary ship Pitcairn under full sail on one of her voyages into the South Pacific Ocean. |

However, while in Fiji they sold out of some book titles, especially the medical volumes. It had been almost twelve months since the ship had left San Francisco, with much of that time spent on the high seas. Personal health reserves were running low, and so plans were revised and the ship sailed for Norfolk Island.

With the landing of the Pitcairn's company at Cascade Bay, Norfolk Island, on September 30, 1891, the Pitcairners on Norfolk were glad to meet their relatives from Pitcairn Island who had come on the missionary ship. Pastor Gates conducted the first Saturday Sabbath service on Norfolk in the home of Jane Quintal, James McCoy's sister, on October 3. Missionaries Read and the McCoys were asked to remain to do missionary work on Norfolk Island, and a few days later the Pitcairn made sail for Auckland, New Zealand, with six passengers as well as a boy to assist Pastor Gates in his missionary endeavors.

The Pitcairn was at Auckland for six weeks before returning to Norfolk, with a call on the way at Kaeo, north of Auckland. While at Norfolk, those on the missionary ship found that a number of people had become interested in the Adventist faith. When the ship sailed again, Mary McCoy stayed at Norfolk, taking up residence with her sister, Jane Quintal.

The voyage to Auckland again from Norfolk was "the most disagreeable trip we have had," said Gates. For ten days the missionary ship had to beat against head winds and high seas, with intervals of dead calm as an extreme to further frustrate sailing progress.

Once at Auckland again the Pitcairn was extensively refitted and transformed from its schooner lines into a brigantine. A cabin galley and forecastle were added, and auxiliary steam power was installed for easier maneuverability among reefs and in time of calm. The refit took about two months.

During the refitting time the Pitcairn's crew members scattered to various locations. First mate Christansen traveled to Sydney, Australia, to sell religious literature among the many nationalities along the city's docks. Others sold books and tracts in the New Zealand countryside, while Pastor Gates and his wife make a speaking tour among Adventists in the cities of Sydney, Melbourne, Ballarat, Adelaide, Hobart, Invercargill, Dunedin, Christchurch, Kaikoura, Wellington, Napier and in Auckland. While they were on tour, the sad news reached them from Fiji that John Tay, the initiator of the whole Pitcairn enterprise, had died on January 8, 1892, of influenza. He was buried in the cemetery that overlooks Suva harbor. His wife took passage on a steamer back to America via Sydney.

Tay's death was followed by another tragedy. The Pitcairn's Captain Marsh suffered a major health breakdown in Auckland. For two months he fought a losing battle against liver and kidney failure and other complications, finally passing away on June 3, 1892.

Upon learning of his captain's death, first mate Christiansen quickly returned to Auckland from Sydney to take command of the Pitcairn. Crewman Gustav Anderson stayed in the Hawkes Bay area to evangelize the many Scandinavian settlers there, and married Miss Esther Kelly of the Napier church. Following some success among his own people, he too suffered severe illness and died on November 29, 1896, at age thirty-four.

Anderson's place among the Pitcairn crew was taken by Mr. McCallum, a non-Adventist Christian who studied the Adventist faith as the ship sailed again for Pitcairn Island. Once at the island, McCallum chose to be baptized as a Seventh-day Adventist Christian. On the voyage from Auckland to Pitcairn Island, the passengers included Pastor and Mrs. Gates, the Reads, James McCoy and Mrs. Marsh with her children. New faces on board were Pastor Will Curtis and his family returning to America after five years service in Australasia. Five New Zealanders also joined the vessel - Mrs. J. Plowman, sixteen-year-old Edith Hare and her younger brother Arnold, John Paap, and Margaret Teasdale. The four young people wanted to further their education in America.

Leaving Auckland on June 26, 1892, it took thirty-seven days to reach Pitcairn Island. It was by all accounts a horrible voyage. Lashed by severe storms with the ocean surface like whipped snow, the Pitcairn suffered a sail blown to pieces before the rest could be stowed below deck. The crew tied an oil keg to the ship's windward side to help break the crashing seas, and lowered the storm anchor. Ropes were stretched across the deck to assist the crew who were in almost constant danger of being swept overboard. Day after day the missionary ship was battered by the merciless elements. Passengers were not allowed on deck. Curtis reported, "Great mountain-like waves, with their foam-crested tops towering far above us, came rushing on as though they would entirely pass over us. The roar of the ocean was terrible!"

Pastor Gates' dyspeptic health fared badly in the storms of the voyage back to Pitcairn Island. His wife also did poorly. They decided to minister among the Pitcairners for a year, hoping to regain their health rather than risking more bad weather on the way to San Francisco. The Reads decided to locate on Tahiti. They disembarked at Papeete on August 25 and began nurturing a nucleus of those interested in Bible study, being the first resident Adventist missionaries in the Society Islands.

The Pitcairn sailed through San Francisco's Golden Gate on October 8, 1892, after almost two years abroad. Experience taught the missionaries that subsequent voyages should be of shorter duration. Poor nutrition during sea-sickness bouts, disturbed sleep, and lack of proper exercise in such a confined space proved to be major factors injurious to their health.

Reflecting on the Pitcairn's mission enterprise, the church took comfort in the knowledge that Adventist book sales among other missionaries, literate islanders, and European settlers were a resounding success. That literature, they knew, would influence many to accept the principles of the Adventist faith. In addition, a church was firmly established on Pitcairn Island. Furthermore, the Society Islands, Fiji, and Norfolk Island showed promise of a developing interest in the Seventh-day Adventist mission.

The Pitcairn's Second Voyage

In San Francisco, while waiting for another voyage, more improvements were made to the Pitcairn. Better lights and rigging were fitted and the deck cabin was enlarged. A room where visitors could inspect and purchase books was also provided.

Former first mate Christiansen remained the captain for the second voyage. His crew consisted of fresh names - J. Werge, Lars Jensen, John Chilton, James Bennie, Nils Johnson, Ludwig Drenson, and Hansen of the first voyage. Among the supplies were about twenty-two tons of books stowed below deck, together with a windmill and farming implements for Pitcairn Island, and timber for missionary homes.

The new missionaries going to the South Pacific were Benjamin and Iva Cady, John and Fanny Cole, and Elliot and Cora Chapman. Experience taught that books on health and home treatments were eagerly sought in the islands. Capitalizing on this interest, Dr. Merritt Kellogg was aboard. He would give treatments and lectures where the Pitcairn called. Also aboard was Miss Hattie Andre, a recent graduate of Battle Creek College. She would serve as a trained teacher for Pitcairn Island. James McCoy was once again on board, returning to sell books throughout the isles.

Leaving San Francisco on January 17, 1893, the ship arrived at Pitcairn Island on February 19. |

|

The ship Pitcairn tied up to another vessel at the docks in Oakland, California. |

Those on board found that Pastor Gates had spent his time caring for the spiritual needs of the people, building a missionary home after initially living in a tent, and organizing a literary society. From this society came the short-lived "Monthly Pitcairnian," a hand-written publication of news items and pleasantries. Ida Gates had taught school and conducted health meetings for mothers on Pitcairn. Her classes began at 5 a.m., leaving much of the day for normal island pursuits.

Soon after its arrival at Pitcairn, the missionary ship was on its way, with missionaries Cady and Gates and some of the Pitcairners aboard, to Mangareva in the Gambier Islands. The tiny village there was dominated by the Roman Catholic mission. French and Spanish Bibles were sold, and the impression was gained that the islanders would be receptive to Pitcairners as missionaries. Mr. Schmidt, a trader on Mangareva who was unhappy with the education his children were receiving, sent his three children (a sixteen-year-old girl and her two brothers, thirteen and eleven) to attend Hattie Andre's new school that was opening on Pitcairn Island.

Miss Andre's school opened in April 1893 with forty-two students ranging in age from fourteen to thirty-nine. In addition to normal school subjects, she recognized practical talents, teaching the men to make wooden curios and the ladies to do basket-weaving and dried leaf painting. (The large leaves of Bauhinia monandra, which grows profusely on Pitcairn Island, were utilized by Miss Andre, and now are nick-named "Hattie leaves"). This handiwork was then sold aboard passing ships. The younger age group in school were taught by Rosalind Young. Ida Gates operated a kindergarten.

The Pitcairn sailed from Pitcairn Island westward to Tahiti, Huahine, and Raiatea Islands. At Papeete, those on the missionary ship found that the group of those interested in the beliefs of the Adventist faith had grown to nearly eighty worshippers. While the missionary ship was at Raiatea, the population of four thousand pled for a missionary, so Benjamin Cady elected to stay with them. The Chapmans also disembarked at Raiatea, to help with the school and to take charge of translating and printing literature.

Then the ship sailed to Rurutu Island, where Dr. Kellogg treated numerous sick people. From Rurutu, the Pitcairn sailed to Mangaia Island and jumped the reef to allow Kellogg to go ashore and treat more patients. Then it was on to Rarotonga, where Kellogg found there was only one resident doctor for the seven thousand people there. He stayed a week on Rarotonga, performing surgical operations and caring for various maladies.

Continuing west, the Pitcairn visited Niue Island for the first time. It is a mass of coral rock almost bereft of soil, but somehow was managing to support about fifteen thousand people. Dr. Kellogg disembarked from the ship and walked the eight kilometres across the island from Avetele to the main town, Alofi, while the ship sailed around a promontory to meet him again. (The pilot who brought the Pitcairn into port later became a Seventh-day Adventist Christian).

In his walk Kellogg observed a school and native teacher of another denomination in every village. After treating over fifty patients, he concluded there was a real need for medical mission work to be established on the island. He also lamented the fact that Christianity had introduced a spy system into the society. Some, called "holies," reported misdemeanors to the fakafili (judge) and a fine was divided up between the judges and the spies. "The result of this system," Kellogg wrote, "is to cause the people to fear the law instead of fearing God, and as they have but a very dim idea of the object and power of the gospel, they learn to practice deceit so as to avoid detection and punishment."

The Pitcairn spent ten days at Niue before sailing to Vava'u Island, Tonga, where the harbor pilot warned them of a measles epidemic present. Not wanting to be held in quarantine elsewhere, they decided to sail on to Fiji and Norfolk Island. The Coles remained on Norfolk. Kellogg preached there in a private home, and in the Methodist chapel, on the topic of temperance.

When the ship arrived in New Zealand, its company was well received again. Harbor authorities waived entrance fees because the ship was on mission business. In Auckland, Kaeo, and Whangaroa, Kellogg once again gave temperance lectures. Pitcairner James McCoy took separate passage to Melbourne in order to speak to the students at the Australasian Bible School about mission work in the Pacific. The Pitcairn sailed south to Napier and Wellington in time for a camp meeting, held from November 30 to December 12.

While in Melbourne, McCoy learned the devestating news that his wife and a daughter on Pitcairn had died of typhoid fever. He quickly rejoined the Pitcirn in New Zealand and she made haste, arriving at Pitcairn Island on February 6, 1894.

Early Adventist leader Ellen White sent a letter of sympathy with the ship. Not until they arrived did they learn the full extent of the tragedy.

|

|

| The ship Pitcairn with others at Oakland, California, awaits the start of its next voyage to the South Pacific Ocean |

The disastrous chain of events began when the ship Bowden ran aground on Oeno reef on April 23, 1893. The captain and crew saved their lives by rowing the 112 kilometres to Pitcairn in small boats. Soon afterwards they were taken off Pitcairn by a passing ship, but one crew member, suffering from typhoid, was blamed for contaminating the island.

Later, a doctor on a passing ship treated the Pitcairners and they all appeared to recover, but from August to October there was a resurgence of the disease. Miss Andre and the Gates' escaped unscathed even though they spent much of their time nursing the sick and burying the dead. The harrowing experience did, however, drain Gates of his limited health reserves.

James McCoy's wife, Eliza, was the first fatality. Others to die were Ella, one of their daughters; Mrs. McCoy's father and patriarch of the island, Simon Young; two of her brothers, Edward and John; Elias Christian and his son, Willia; Reuben Christian; Martha and Clarice Christian; Childers Young; and two-year-old Emma Christian. Everyone mourned because in their closely-knit society all were interrelated.

Everyone except three or four of the islanders suffered the disease to some degree. All were stunned by its ravage. They were led to conclude that the general health principles being advocated by the missionaries were beneficial and a reformation in living habits took place.

When the Pitcairn sailed for San Francisco, Maude Young, Henry Christian, and a surviving daughter of James McCoy, Wennie, were aboard with plans to further their studies in America. The Gates also decided to return to America to fully recuperate their health.

The voyage back to America was a slow one. The ship experienced strong head winds, and did not arrive in San Francisco until March 30, 1894, forty eight days after leaving Pitcairn Island. Future voyages homeward were thereafter begun from points further west of Pitcairn Island, which allowed for steering in a north-easterly direction and thus catching more favorable winds.

The Pitcairn's Third Voyage

The Pitcairn's third voyage proved to be a brief one compared to other years. Pastor John Graham of the North Pacific Conference of Adventists was chosen to be captain of the missionary ship. Former crew members Werge, Johnson, and Chilton were joined by E. E. Hicks, G. W. Neilson, A. Larsen, R. K. Suhr, and cabin-boy Fred Tracey. Neilson had recently become a Seventh-day Adventist as a result of evangelism in Sydney, Australia.

The Pitcairn continued to take an increasing number of missionaries to the South Seas, some, on this occaion, with their children. Dr. Joseph Caldwell, accompanied by his wife, Julia, and two boys, planned to establish medical work on Raiatea but alterations occurred later. Other missionaries on board were George and Ada Wellman; Rodney and Carrie Stringer; W. E. Buckner and his wife, Rosa; Dudley and Sarah Owen, together with their two children; and Miss Lillian White. At least three of these families - the Buckners, Owens, and Stringers - came as self-supporting missionaries. Maude Young was returning to her Pitcairn home, and James Russell McCoy of Pitcairn was also on board. Tied to the deck was a pile of lumber to be used for building missionary homes. Maximum use was made of all space on the ship.

Leaving San Francisco on June 17, 1894, the Pitcairn arrived at Pitcairn Island thirty days later. Northerly winds generally drove the ship fast until they reached the unpredictable equatorial zone. There they often had calms, frequent rain storms from every direction, and choppy seas. This particular 6,500 kilometre voyage was punctuated with gales and sea-sickness aplenty.

The weather was so wild upon arrival at Pitcairn that the crew doubted if a boat could be launched from Bounty Bay to come out to meet them. But as they peered into the distance they saw a small black speck on the crest of the waves. It would appear, then disappear in the trough of the seas.

|

|

The ship Pitcairn along with others at Oakland, California, awaits the start of its next voyage to the South Pacific. |

A few brave Pitcairners in their longboat had battled a path toward the Pitcairn and before long the oarsmen were throwing oranges into the eager hands of the weary travellers on the ship. Against the howling winds the islanders shouted instructions to the captain to go to a relatively sheltered spot on the island's north coast. There the missionaries were ferried through breakers.

Captain Graham swooned as he alighted. For him the shore appeared to be moving just as violently as his ship. Buckner was so weak from sea-sickness that he had to be carried up the steep hill and wheeled to the village in a wooden wheel-barrow. McCoy and Caldwell were soon after overturned into the sea and had to swim ashore while unloading freight from the Pitcairn. The longboat was wrecked on the rocks and all its contents lost.

The Buckners remained on Pitcairn as self-supporting missionaries. His aim was to supervise the building of a boarding school, and to improve the system of water supply to guard against further outbreaks of typhoid fever.

When the Pitcairn sailed from the island, Maude and Sarah Young joined the group as missionaries too. They had given training in simple medical remedies.

On arrival in Papeete, the Pitcairn ran headlong into an icy reception. Cady's work at his Uturoa station on Raiatea Island, and at nearby Avora where the French Roman Catholic mission was located, was having a telling effect and objections had been lodged with the governor in Tahiti. Anticipating angry scenes, the governor issued the captain a letter insisting that the Pitcairn not proceed to Raiatea. He also commended that he preferred any missionization to be done by the French rather than Americans or British. Caldwell, therefore, realized he was not welcome and decided to move on. The Wellmans and Lillian White, nevertheless, disembarked at Papeete to await developments.

Avoiding Raiatea the Pitcairn sailed to Huahine Island. After reporting to the customs officer they visited the queen-a sixteen-year-old girl whose government was cared for by a regent. Then they visited the native pastor of another mission group. He did not relish their call. Indeed, when the missionaries attended the Sunday service, prayers were said both blessing and damning the Americans. A lay preacher asked for a blessing on the Pitcairn, but the native pastor asked the Lord to drop fire from heaven and consume the boat with its occupants.

The Pitcairn next sailed south to isolated Rurutu Island which was not directly under the control of the governor in Papeete. Another regent ruled Rurutu because their local king was still a minor. This regent had received a warning letter from a mission group unfriendly to Adventists. Nevertheless, as soon as Stringer was ashore he began gathering some natives around him, extracting and filling their teeth. The islanders also learned he was something of a blacksmith, farmer, and nurse. Prejudice broke and the regent allowed the Stringers to stay as self-supporting missionaries. Pitcairner Sarah Young also remained to assist.

Captain Graham then set sail for Rarotaonga where the real pioneers of the Cook Islands, the Owen and Caldwell families, disembarked. Here, Caldwell was more welcomed. The Reads, who had come with Graham from Tahiti, helped to establish the new missionaries.

Owen searched the island and found housing and land difficult to rent. The governor finally allowed them to move into a substantial home built for himself but which he had never used. There was land enough to keep a cow, horse, and extensive gardens. Instead of paying the rent they receive US$110 a year to act as caretakers! Pitcairner Maud Young assisted Caldwell in what became known as the Avarua Adventist Hospital.

Having come so far with urgent supplies for Cady, Graham thought it best to approach the governor in Papeete once more. After a rough passage he arrived at Papeete on October 30 with his renewed request. Reluctantly, this time the governor gave Graham permission to land at Raiatea providing he unload only at the village of Uturoa and not arouse the French missionaries by exploring elsewhere. This they did as quickly as possible, and the Pitcairn sailed for home, arriving in San Francisco on December 27, 1894.

The Pitcairn's Fourth Voyage

The 1895 cruise of the missionary ship Pitcairn left San Francisco on May 1, with John Graham

as captain again. His young son accompanied him. Once again, Hansen, Suhr, Werge, Nilson, and Chilton were crew members.

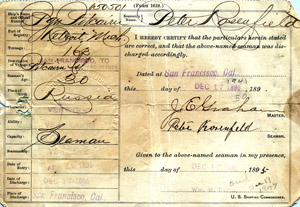

The new crew members were Peter Rosenfeldt, Christopher Treulieb, and cabin boy J. E. Floading.

Reinforcing the medical wing of missions, Dr. Frederick Braucht and his wife, Mina, traveled together with Edwin and Florence Butz and daughter, Alma; Edward and Ida Hilliard and daughter, Alta; Jesse and Cora Rice and child; as well as Rowen Prickett and his wife, Pauline. A Tahitian girl, who had gone with the Reads when they returned to America to take a medical course, was also on board, bound for her homeland.

Thirty-six days of sailing brought them to Pitcairn Island again. They found that since their last visit the Pitcairners had been busy felling timber and building a boarding school.

"We are trying to race the Avondale project in Australia," Hattie Andre chuckled. The buildings were completed. However, for various reasons her vision of making Pitcairn a center for training missionaries did not mature.

The island was a center of Adventist mission in the early 1890s, and many Pitcairners left to evangelize elsewhere, but as other centers in the South Pacific were developed Pitcairn's extreme isolation made it impractical as a boarding school. It proved difficult to attract students from other places, even from the nearby Gambier Islands.

|

|

The shipping papers of Peter Rosenfeld who was a crew member on the ship Pitcairn's fourth voyage into the Pacific Ocean from San Francisco. |

The Butz family remained on Pitcairn temporarily to assist Miss Andre in her school, and Pitcairner Alfred Young went with the Pitcairn to attend college in America. James McCoy's daughter, Emily, also sailed on the ship for the purpose of assisting Dr. Braucht in his medical work.

On the missionary ship's arrival in Tahiti, the Wellmans and Lillian White boarded for transfer to Rarotonga. The ship also picked up the Chapmans who were returning to America on account of Cora's declining health. The Pricketts took up the translation and printing work established there by the Chapmans, and assisted Cady wherever possible.

Leaving Papeete, a call was made at Raiatea and then Rurutu where the Stringers were found to be settled and respected by the local people. A brief call was made at Rimitara Island also. Here the ship's company dined with local royalty and, with Cora Chapman as interpreter, sang hymns in English and Tahitian as a mark of friendship.

At Rarotonga, the Rice and Wellman families, together with Lillian White, disembarked to assist Caldwell and Pitcairner Maud Young in their little hospital and pioneer schools on the island. They were shocked to learn that once more a missionary had paid the supreme sacrifice: Sarah Owen, Mina Braucht's mother, had died on July 9. (The Owens had arrived on the Pitcairn's previous voyage). The London Missionary Society agreed for the funeral service to be held in their church, with interrment in the little cemetery alongside. Dudley Owen and his children, bereft of wife and mother, were a pitiable little group as they boarded the Pitcairn to transfer elsewhere. To keep the family together they thought it best to settle wherever the Brauchts were to establish themselves.

The Pitcairn delayed its departure from Rarotonga until the local parliament dismissed. Twenty-four officials then took passage on the missionary ship to Aitutaki and Niue.

The Hilliard family continued with the ship and settled on Tongatapu Island, becoming the first Adventist missionaries to reside in the Tongan group. Ida Hilliard taught a school in her home, giving Bible lessons each day.

John and Fanny Cole, with their little baby girl, Ruita, had transferred from Norfolk Island to the old capital of Fiji, Levuka, in mid-1895. Little had been done in Fiji since the death of John Tay three years earlier.

Before Cole left Norfolk he baptized five people and organized their church. Among those baptized was the island schoolmaster, Alfred Nobbs, together with his wife, Emily. In their closely-knit Anglican society those who broke from the traditional habits were maligned. Tensions grew worse when Nobbs destroyed all his pigs rather than give them to his brothers as the relatives thought he should.

Stephen and Melvina Belden had transferred from Sydney, Australia, to help strengthen the infant church on Norfolk. They were in their mid-sixties and became friends with Nobbs but the church lacked a minister for a decade. The mission on Norfolk languished when Cole left for Fiji. Its loss was Fiji's gain.

Dr. Braucht thought to establish himself in practice in Fiji but the medical licensing authorities said his qualifications did not meet their requirements. For that reason he continued on with the Pitcairn to Apia, Samoa, where he did gain acceptance. Owen, his father-in-law, assisted him in pioneering among this group of islands.

Leaving Apia in late October, 1895, the Pitcairn sailed directly for San Francisco, arriving at the California port city in early December 1895.

The Pitcairn's Fifth Voyage

With John Graham continuing as Pitcairn's captain, the fifth voyage set sail for Pitcairn Island

on May 19, 1896. With him again were crew members Hansen, Werge, and Rosenfelt. New crew included J. E. Patterson, John Peterson, M. Benonisen, and Mr. Ellingsen. The cabin boy was Daniel Fitch who later grew up to be a minister in America. This fifth voyage proved to be as long as the arduous first voyage in terms of distance covered, but the ship was not away from home port so long.

The new missionaries on board were Herbert and Millie Dexter; Joseph and Cleora Green; Jonathan Whatley and his wife, Sophie, as well as their son, Roy; together with William Floding, a nurse. Pitcairners Alfred and Arthur Young were also returning to Pitcairn after attending Healdsburg College in Northern California, the forerunner school of Pacific Union College.

The ship's company arrived off Pitcairn Island in a moonlit night after thirty-two days of sailing from San Francisco. They rolled up lengths of paper, soaked the tips in oil, lit it and waved the improvised torches to attract attention on the island. Someone ashore spotted the lights and the longboats were launched. By 2 a.m., the Pitcairners were rowing the missionaries ashore for a six-day stay. |

|

|

The ship Pitcairn Pitcairn's missionariy contingent on her fifth voyage had this photograph taken on May 18, 1896.

|

When the Pitcairn sailed from the island, only Whatley and his wife remained behind to teach, with islander assistance, in the new industrial school modeled on one in Texas. The two dormitories and a dining hall with kitchen complex had been completed, opening New Years Day 1896.

After three years of teaching, Miss Hattie Andre was returning to America, sailing on the Pitcairn only as far as Samoa where she took passage on a steamer. She was the poorest of sailors in small boats, growing bilious even in a gentle swell. The Buckners, too, returned to America on the regular mail vessel from Tahiti.

At Pitcairn Island the Butz family also boarded the missionary ship for they were under transfer to Tonga, taking with them Pitcairner Maria Young and Tom Christian as assistants. Once again, Pitcairner James McCoy joined the ship to work wherever needed. So also did Pitcairner Rosalind Young, poetess, teacher and historian of Pitcairn Island.

When the group arrived in Papeete, Tahiti, they found Cady's home school operating with seven students. From his experience with the school on Raiatea he concluded that the influences of the local society, or, more particularly, the absence of any positive influence, broke down many of the moral values he was trying to teach. For that reason the missionaries took a small number of the students into their homes where they lived as part of the family units.

In Papeete, some adult converts continued to worship with the missionaries. Bambridge was still with them. Three French women, Paul Deane, and some other Tahitians comprised the core of the believers. About twenty kilometres awy, at Paea, another small group had grown and were wanting to build their own church. Dexter, who had spent his boyhood in Tahiti, remained with Cady to nurture the expanding Adventist community.

The Greens also disembarked at Papeete in order to continue the printing work, supplying literature for the Society and Cook Islands. This was necessary because the Pricketts were transferring to Rarotonga to assist Caldwell in medical missionary work.

From Tahiti the Pitcairn sailed to Rurutu against strong headwinds, finally arriving on July 31. Rough seas on the west side of the island where the Stringers lived made a landing impossible. The ship was forced to the east side where they disembarked and spent the night in the young king's village. The following day they found the Stringers and Pitcairner Sarah Young undaunted despite some earlier seasickness and other problems. Rats had eaten their vegetables growing in the garden and wild cats had killed their hens. Nevertheless, they were learning the language, and the islanders were beginning to appreciate some of the Adventist message. Sarah Young left the Stringers at this stage to assist elsewhere.

A brief stay of four days at Rurutu came to an end and the Pitcairn set sail for Avarua, Rarotonga, to visit the Caldwell and Rice families. There they found the government had equipped a building for hospital work. Dr. Caldwell was the appointed medical superintendent, with Pitcairner Maud Young as chief nurse. The Rice family, living in the second largest village nearby, were doing well with their school. Timber, doors and windows were unloaded for them to build a small house for themselves.

Before reaching Samoa the missionary ship made two calls. The first was at Aitutaki atoll where the people were disappointed to learn the Pitcairn could leave them no teacher-missionary.

The second stop was the ship's first visit to Palmerston atoll where, about forty years previously, an English sailor had settled. His twenty-three children and their families, a meager population of forty-three, all spoke English. The missionaries were invited to preach at their regular church service. (A native missionary of another denomination had been stationed on the atoll). Bibles and school books were left with these people before sailing on to Apia.

In Samoa they found Dr. Braucht was establishing himself in medical missionary work. Dr. Kellogg and his new wife, Eleanor, whom he had married in Australia, had arrived earlier. Kellogg was superintending the building of the mission hospital at Apia and Owen was assisting him. Floding was left to help Braucht and then the Pitcairn sailed south for the Tongan Islands.

The ship arrived at Tongatapu Island on August 29. Pitcairner Sarah Young disembarked to help the Hilliards in their Home. The Butz family, together with their house assistant, Pitcairner Maria Young, also settled there.

A Tongan-language paper against Adventists was circulating in the area, having originated with another mission group, but Hilliard seemed of good courage. He reported he was learning the local language, and in his initial twelve-month stay some locals showed interest in studying the Scriptures with him.

At this juncture Rosalind Young was forced to return quickly to Samao and catch a steamer to America. She was diagnosed as suffering from a fast-growing tumor and needing specialist surgery.

The Pitcairn continued on to Fiji to find the Cole family ailing and in need of a furlough. Just four months earlier some assistance for them had arrived from New Zealand in the persons of Pastor John Fulton and his wife, Susie. They, of course, brought with them their two little daughters, Jessie and Agnes. Edith Guilliard, a fifteen-year-old Napier, New Zealand girl, also accompanied them as house assistant.

Captain Graham determined to make the return voyage home a reconnaissance cruise skirting Vanuatu and the Eastern Solomons, then sailing across the North Pacific to San Francisco. There was growing concern among church administrators over the ship's operating costs. Weighted against the lack of dramatic baptismal figures (except for Pitcairn Island), figures on paper indicated that a reassessment of the whole mission venture was overdue.

English and French traders as well as plantation owners, were already living in the Western Pacific. Roman Catholic and Protestant mission groups were already established. By comparison to the Eastern Pacific it was a much more inhospitable region. Tiny coral islands which can be traversed in less than a day are prevalent in the East. The Western island groups, however, are characterized by rugged terrain and dense jungles. Disease seemed to be more prevalent and cannibalism was still rife.

The Pitcairn plied its way among these islands making courtesy calls at the Presbyterian mission near Port Vila and a medical mission station on Ambrym Island, Vanuatu. Further stops were made at Port Stanley on Malakula Island and Port Patterson in the Banks Islands.

Sailing north to the Santa Cruz Islands they by-passed Vanikoro and Utupua Islands because the inhabitants were infamous for their treachery. Islanders rowed out to intercept the Pitcairn, and some more courageous ones boarded the boat in a bid to trade curios for tobacco. Eventually they realized there was no "tobac" on board and were content to trade for other items. Graham pressed on and called in on Mr. Forest, a missionary-turned-trader, on Nendo Island.

Near the equator the Pitcairn arrived at Pleasant Island (Nauru), controlled by Germany. Captain Graham went ashore in a dingy. The government authorities, on learning of his mission, quoted the law saying, "Any religious teachers establishing themselves on the island without permission from the German authorities in the Marshall Islands were liable to a fine of one thousand marks or six months in goal." Graham noted, however, that the indigenous people had a smattering of Christianity and were very receptive. He reported, "We have not visited a place where we felt a greater desire to leave missionaries than here."

Any hope of leaving perhaps one of the Pitcairners on Pleasant Island was dashed by the Brusque welcome at Jaliut in the Marshall Islands. Almost becalmed ten miles offshore, Graham decided to take the dinghy in to the harbor with Hansen, Fitch, McCoy, and Christian as oarsmen. They had to row against strong currents for over three hours, but once again the German authorities curtly told them their mission was not wanted. They reinforced their displeasure by reminding Graham of the huge fine which could be levied, so the captain and his men took to the oars again, reaching the Pitcairn just as night was settling over the sea.

On the following day, October 14, 1896, the Pitcairn started on the long voyage across the North Pacific Ocean to San Francisco, a distance of some five thousand kilometres. Captain Graham concluded, "The blessing of the Lord has been with us and His protecting care over us as we have sailed among the dangers of the sea, and to Him we give all praise."

The Pitcairn's Sixth Voyage

For six consecutive years the Pitcairn had plied the Pacific Ocean. When this dame of the deep tied up in San Francisco in 1896 she was not to leave again for over two years. Lack of finance was the chief cause. However, the isolated missionaries grew desperate for supplies so a further trip was planned. The ship did not sail until January 23, 1899. During the interval Pitcairner James McCoy worked as a ship missionary in San Francisco harbor.

There were no new missionaries on board for the sixth voyage. Edward Gates, as leader of the island mission work, went on the voyage with the express purpose of staying briefly at each island group to assess progress and future needs. William Crothers, at that time a bachelor who had already served in New Zealand selling books, was on board after a respite in his homeland. Pitcairner Ben Young was returning to his island home. Less personnel aboard meant that more cargo could be carried. Lumber to build dwellings in the Society Islands and a portable church for Tonga were among the bulky items put on board.

Werge was promoted to captain of the Pitcairn for her final voyage. His crew was entirely new - A. Andreason, E. Bersinger, F. C. Butz, E. Wigley, J. O. Harrison, T. Bennet, C. L. Harvey and cabin boy William Hiserman.

After an absence of over five years Gates was glad to visit with his beloved Pitcairners again when the Pitcairn reached the tiny isle. While Gates and Crothers remained on Pitcairn, James McCoy and the crew sailed to Mangareva Island in the Gambier Islands to sell French and Spanish Bibles again.

At 5 a.m., on almost every day while he was there, Gates held revival meetings. His stay was climaxed with yet another baptismal service, this time for a number of young people and those who had fallen away from the faith.

While Gates was with them, the Pitcairners decided to pay tithe from their gardens. This produce was sold to finance mission expansion. The habit grew of marking each tithe coconut with the letters "LX," meaning "The Lord's Tenth." Gated encouraged the need for the Pitcairners to own a small ship of their own to take produce to the Gambier Islands rather than simply depending on the occasional sale to passing ships.

Three weeks were spent at Pitcairn Island before the missionary ship sailed for Papeete, Tahiti. Once again they were met by the Cadys at Papeete. The Greens were preparing to return to America because Joseph was ill. Stringers had transferred to Papeete the previous year after battling against difficult odds for four years to try and generate an outpost on Rurutu Island. Stringer himself was about to supervise the building of a church in Papeete. One had already been built in nearby Arue. Funds were being gathered to build a third church at Paea.

Cady was anxious to sail to Raiiatea with the Pitcairn. He had bought a plantation of four thousand coconut palms which he planned to develop into an industrial school and training center for island missionaries. There were some Sabbath-keepers in the area but they were not organized into a church at that stage. The ship stayed at Raiiatea a little over a week and then sailed for Rarotonga.

Gates sounded travel weary as he recorded his observations in the Cook Islands, but was happy to see the Caldwell and Rice families again. "After having been at sea for weeks and months, and having suffered from seasickness, these meetings with brethern and sisters on the little dots of land in mid-ocean are precious experiences," he wrote. In his opinion, an industrial school similar to Cady's was needed in the Cook Islands too. The missionary families were, for the time being, taking a few local children into their homes to train them. At least one adult had already accepted Adventism - Frances Nicholas, who was attending the Avondale School in Australia.

While at Rarotonga a quick trip was taken to Aitutaki atoll enabling Caldwell to treat many cases on the spot. The local people there offered a house and land for a branch medical mission but staffing it was an impossibility.

On May 8, 1899, the Pitcairn sailed from Rarotonga to make calls at mission outposts in Samoa, Tonga, and Fiji. They arrived in Samoa in mid-may. Gates made the observation that opportunities abounded for more self-supporting missionaries to come to Samoa.

When they reached Tonga on Sabbath, June 3, they found all the missionaries were in good health and using the native language. Up to this time the Hilliard, Kellogg, and Butz families had concentrated their efforts on Tongatapu. The Pitcairn therefore transferred the Butz family further north to Vava'u Island.

At this time some of the missionaries were leaving to attend the 1899 Australasian Union Conference Session at Cooranbong, Australia. Moves were already afoot to administer the southern Pacific region from Australia rather than America. Gates, therefore took a steamer with Hilliard to Auckland and Sydney while the Pitcairn plied its way to Fiji.

Captain Werge sailed for Fiji on June 13, 1899. Ill health had forced the Cole family to leave Fiji and return home. Calvin and Myrtle Parker, with their little girl, Ramona, had already come from America to fill the gap.

When the Pitcairn called at Suva, Fiji, the Fulton and Parker families were eagerly waiting because they had received word of something special aboard for their work. Cole had written from America saying he had raised enough money to buy a Columbian lever press as well as a font of type, and was planning to send it on the ship. They were not disappointed. To stop it sliding around inside its crate, Cole had packed the press in California dried prunes. What a bonus! While the Pitcairn was preparing to return to San Francisco on what was to be her last trip to her home port as a missionary vessel, reports were circulating in newspapers around the world of great wickedness and moral depravity on Pitcairn Island. In Australia, Gates acknowledged that while there was truth to some of the reports, the majority of them were without any factual basis. Indeed, there had been a murder of a young Pitcairn woman and her child, but the majority of the Pitcairners were wonderful, believing Christian people.

As Captain Werge steered the missionary ship northeastward for the last time, he and the many others who had sailed on the Pitcairn knew that God has used them mightily to plant seeds of truth in the hearts of thousands in the Pacific Isles.

Assessing the Advent of the Pitcairn

Six voyages over a period of ten years had absorbed tens of thousands of dollars as well as the energies of scores of missionaries. This Advent thrust into the South Pacific was a bold one. The missionaries were motivated by Scriptures like Isaiah 42:4, Matthew 24:14; 28:19,20, and Revelation 14:6. By the end of the decade it was time to take stock.

Prior to the Advent of the Pitcairn scores of martyrs had fallen in the Pacific Islands. More were to follow.

Fifty American Seventh-day Adventist Missionaries, and a number of Pitcairn islanders served in the Pacific during the time of the Pitcairn. In addition, eight or nine crew members for each voyage were required in the vital task of transportation. Some of the crew had taken a leading role selling Christian literature. Four of the missionaries died in their attempts to spread the Adventist message - Cudney, Tay, Marsh, and Sarah Owen. Six others suffered premature deaths, arguably due to the delayed effects of tropical living conditions - Anderson, Green, Stringer, Julie Caldwell, Pauline Prickett, and Hattie Read.

In most places the missionaries found a genuine welcome wherever they anchored. Initial acceptance did, however, sour in some places as proselytes were gained. For this reason it became increasingly difficult for doctors to retain their acceptance with local government authorities and the medical mission work, especially in the Cook and Tongan Islands, fell on hard times. Furthermore, French authorities in the Society Islands were piqued at the presence of foreign missionaries.

The large number of missionaries engaged in the work appears impressive at first glance. However, they were scattered over a vast area and served only a brief term before sickness overtook them or they transferred elsewhere. In many cases, after first learning the local language and becoming accustomed to the new society it was unfortunate that they then moved on.

In a talk at the 1901 General Conference Session of the Seventh-day Adventist faith, Cady warned against imagining the Pacific Isles to be an "easy field" where Adventist missionaries would be more appreciated than at home. He said it was not a place for people who were attracted merely to the prospect of traveling overseas. "I have found," he said, "that when these people reach the islands, they want to travel home just as fast as they can go." He lamented, "While we have had quite a large number of missionaries to go these islands, at the present time we find that most of them have returned."

Cady himself was an exception to the short tenure of service. Statistics proved the value of this longer residence is just one island group. Gates, in his assessment, could not help but notice that the highest membership was in the Society Islands where Cady served and where almost eighty were baptized.

Sixty members remained on Pitcairn, the drop in numbers being due to the 1893 epidemic, and emigration for personal or missionary reasons. About twenty converts were registered for Fiji, and ten for Tonga. Seven had been baptized on Norfolk Island. Two or three were baptized on Rarotonga, but none in Samaoa.

And yet, according to one Adventist writer: "The ten years of the Pitcairn's missionary journeyings, and the direct contact it made with the great, un-entered territories, together with the keen interest and inspiration it awakened at home and aboard, have exerted an influence which will be felt throughout eternity. And when the Master Mariner closes His log book on the last voyage of earthly life, He will take one fond look at the course traversed by the Pitcairn and will reckon its worth among the larger services of His people."

At the Australasian Union Conference Session of the Adventist faith in July 1899, reports were given of the progress in the Pacific. It was a time, too, when the growing success of the Avondale school in Australia was advertised. It became apparent that Cooranbong, where the school was located, would be an ideal base from which Gates could foster enthusiasm for missions among the students and administer his island mission work. Sailing the Pacific continually on a squeamish stonach was something Gates wished to avoid. He stayed on at the Avondale school after the church business session conducting classes in missions and supervising translation work.

Gates requested that the printing work, formerly done in Papeete, be transferred to Cooranbong. This was done and Chapman came from America the following year (1900), bringing with him more equipment which was originally earmarked for establishing a printing office in Rarotonga.

These events represented a major shift in the development of mission work in the Pacific. It heralded the phasing out of American missionaries, and the introduction of those from Australasia who had trained at the Avondale school.

The American Foreign Mission Board agreed that Gates should administer the island field from Australia, and it was voted to sell the Pitcairn.

The Pitcairn In Commercial Service

It was not long after the Pitcairn returned to San Francisco from sixth voyage that the ship was sold. The church's General Conference Bulletin of April 7, 1901, recorded the particulars:

"The board, after due consideration, has seen fit to sell the brigantine Pitcairn. We received for the same $6,500 - $600 in cash, the balance in a note."

Marine documents record that the ship was sold to W. E. Nesbitt of San Francisco early in 1900, and her name was changed to Florence S. On March 6 of that year she sailed for Cape Nome, Alaska. Late in 1900 she left San Francisco for a three month's cruise in Mexican waters, and on February 22, 1901, the ship sailed for Manila, Philippine Islands.

Little is known about the activities of the ship in the Philippines until October 17, 1912. A copy of a marine document records in part the fate of the ship as of that date:

" . . . that the vessel was lost by stranding on the island of Mindora, Philippine Islands, on October 17, 1912. The "Merchant Vessels of the United States" for the fiscal year 1913 shows that "there were eight persons on board when the casualty occurred, but none were lost."

-o-

Another account of some of -

The Pitcairn's Final Days

From The Marine Digest, September 6, 1941

From Capt. John F. Blain, Northern Pacific district director of the Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation in the first World War period, additional data has been obtained on the two-masted schooner Pitcairn. As told in The Marine Digest on July 16, last, she was built by the Turner yard at Benicia, California, in 1890 for the Seventh-day Adventist church as a South Sea missionary boat. After her first voyage she was re-rigged as a brigantine.

Later she was bought from the missionary organization by the Arnold firm of San Francisco for the Mexican trade, Capt. Blain recalls, and still later Arnold sold her to the Clark and Spencer interests of Manila.

Capt. Blain, then 22½ years old, was appointed master by the Manila owners, the Pitcairn being his first command. He was probably the youngest master on the Coast at that time. He took command in San Francisco, and loaded with Sperry flour for Manila, the Pitcairn was towed out at the Golden Gate in a heavy fog on the fateful day of February 22, 1901. In the fog they passed the dim outlines of a large steamship, the Pacific Mail liner Rio de Janeiro. A few hours later the liner was wrecked in San Francisco harbor with a lost of 128 lives, giving the Coast a sad date.

The brigantine Pitcairn got to sea in good time despite the fog and she made the run to Manila in 70 days. At Manila Capt. Blain was met by Stanley Allen, then of the Sperry organization, now of the Fisher Flouring Mills of Seattle.

After delivering the Pitcairn to her Manila owners, Capt. Blain went master of the United States' inter-island army transport Custer. "The Pitcairn voyage," he says, is one of my pleasantest memories of the sea. She was a smart vessel and could sail like the devil." For the past six years, Capt. Blain has been president of the Charles H. Lilly Co. of Seattle, operating in the seeds, grain, feed and fertilizers business

--Herbert Ford, Director, Pitcairn Islands Study Center |